This is an excerpt written by Ellen Vaughn from Being Elisabeth Elliot.

Soon after Elisabeth and her daughter Val moved into their new home, on November 22, 1963, Val was at school, and President John Kennedy was campaigning; riding in a fin-tailed, open-topped black limousine in Dallas, Texas. The waving crowds, craned to get a view of JFK and Jackie, so elegant in her pink Chanel suit and her matching pillbox hat. She carried a bouquet of blood-red roses as she and the president waved to their fans.

A businessman named Abraham Zapruder, his state-of-the-art 8 mm Bell & Howell Zoomatic movie camera in hand, stood on a narrow four-foot concrete abutment on the parade route as he filmed the colorful procession.

Texas governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie, rode in the limo seat in front of President Kennedy and the First Lady. Nellie turned around. "Mr. President," she called above the crowd noise, smiling big, "you can't say Dallas doesn't love you!"

A few seconds later there was a rifle shot, unnoticed in the roar of the crowd. Then another. The president and Governor Connally were both hit, though not mortally. Then came the third shot, the one that Abraham Zapruder's film captured taking off the top of the president's skull, blowing a pink mist in the air and spewing part of his bone and brain matter onto the back of the limousine. There was Jackie Kennedy, crawling in that primal moment of horror onto the trunk to retrieve it; a Secret Service agent threw himself into the car and it screeched toward the hospital as Jackie cradled her ruined husband in her arms.

Elisabeth Elliot did not own a television, but she devoured everything the print media published about the tragedy. She quoted a New Yorker editorial about the national experience: "It was as if we slept from Friday to Monday and dreamed an oppressive, unsearchably significant dream, which, we discovered on awaking, millions of others had dreamed also. Furniture, family, the streets, and the sky dissolved; only the dream on television was real." She poured over Life magazine's November 26 issue, which featured still shots of Abraham Zapruder's chilling video.

Elisabeth related with JFK's wife, suddenly widowed by unthinkable violence. She wrote to her family, "The movie footage reproduced in Life last week is terribly moving, isn't it? Just what do you suppose Jackie was thinking when she crawled over the trunk of the car? The captions say, 'a pathetic search for help.' I doubt that. I doubt that she knew—or would remember even now—what she was doing. What a thing. I can still scarcely believe it."

Thanksgiving 1963 was five days after the president's death. Elisabeth and Val went to New York's Thanksgiving Day parade at Central Park. There were Donald Duck and Popeye balloons that were a block long. "It took about 45 men, holding on for all they were worth to the guy lines, to keep the monsters from taking off over the skyscrapers." They celebrated Thanksgiving in the Philadelphia area with family friends, then returned to New York on their way home.

Val was part of a Christmas pageant with other kids from her school. Elisabeth baked pies and filled her mantel with pungent pine fronds from her woods. Snow fell. Thrilled about the concept of sledding for the first time in her young life, Val climbed confidently on her new red Flexible Flyer, her head facing downhill, lying on her back. Elisabeth had to set her straight. Meanwhile, their new puppy, Zippy, barked frantically and leapt through the drifts. Elisabeth had gotten him for free from an acquaintance in town. He was "part Walker hound (whatever that is), part Collie, and I don't know what else. He is very roly-poly and cute, mostly white with very badly arranged black patches."

Though not a genius, Zippy Elliot would be an enthusiastic companion for Elisabeth and Val, always ready to explore the woods, his snout vacuuming the narrow trails, quivering with excitement. He accompanied Elisabeth everywhere, waiting in the car while she shopped in town, lying next to her chair by the fire at night after Val went to bed. She tolerated in him what she did not accept in humans, forgiving his untidy behaviors. He would pull paper from her trash can and chew it to bits. Even though he knew she did not "like to have my wastebasket emptied thus," she wrote that "he does it so unobtrusively and humbly, he knows he can get away with it." Occasionally his sins were more flamboyant, as when he ate a tassel off the new guest-room bedspread . . . or when he pulled down and devoured Elisabeth's roast pork and baked potato one night when she left the table to take a phone call. She loved him anyway.

On Christmas morning, 1963, as Elisabeth and Val celebrated in the white snows of New Hampshire, Elisabeth's parents, Philip and Katharine sat at their breakfast table. Philip seemed distracted. He anxiously looked over his left shoulder as if someone were behind him. Again. After the second time, his wife asked him what was wrong. No response. A moment later he looked over his left shoulder again, wide-eyed, and gave no recognition of having heard Katharine when she asked him what he was doing.

Worried, Katharine called some friends—a Mr. and Mrs. B.—they had planned to visit later that day. They arrived within minutes. They sat down together, and Mrs. B. read the Bible out loud. Philip continued to look over his left shoulder. Mr. B. walked him around the house to show him no one was there.

Later, Philip recovered sufficiently for the guests to return to their home, and later Phil and Katharine made their way there to open Christmas presents together. Suddenly Phil looked over his shoulder, turned in a tight circle, and fell to the floor, convulsing, groaning, and vomiting. As they flurried to help him, Mrs. B. heard Katharine whisper a frantic prayer: "Oh, Lord, take him quick, and take him easy!"

At the hospital, Philip stabilized, so Katharine returned home to welcome Christmas guests, who would accompany her back to the hospital . . . and during that interim, her husband passed away. He had gone quick. And easy.

Later, Mrs. B. told Katharine she had had a vivid dream early that Christmas morning. In it, she asked, "Why is this Christmas so different?" An unknown voice answered her. "Because there has been a death in the family."

Later that afternoon, of course, she discovered what her dream had meant.

After the flurry of the funeral, Elisabeth wrote to her mother with empathy. She'd been a widow for eight years now and knew the shock of sudden loss.

...God's time has come for you to be alone, He will be your portion as He promised, and you will find a new kind of life with Him.

Elisabeth Elliot

"I know that you loved Dad, and your life was happy together, and I know too that now that God's time has come for you to be alone, He will be your portion as He promised, and you will find a new kind of life with Him.

"Remember that word about our 'light affliction'—it is working for us a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory. I don't know what this means, but I know it must be wonderful.

"Do not waste any time or energy in self-reproach for what you didn't do for Dad, or what you might have said which you now regret, etc. This is a natural reaction, but useless and probably results from a distorted view.

"I love you, Mother, and trust God to prove His own love to you.

1 EE to "Dearest Folks," December 10, 1963.

2 EE to "Dearest Folks," December 3, 1963.

3Account of Elisabeth's dad's death to her siblings Phil, Dave, and Ginny, January 10, 1964.

4 EE to "Dearest Mother," January 8, 1964 (the 8th anniversary of Jim's death).

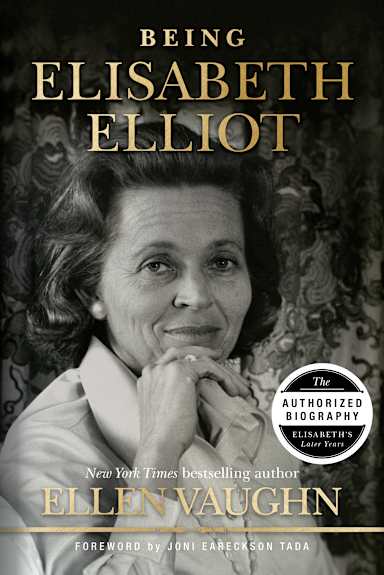

Being Elisabeth Elliot

Elisabeth Elliot was a young missionary in Ecuador when members of a remote Amazonian indigenous people group killed her husband Jim and his four colleagues. And yet, she stayed in the jungle with her young daughter to minister to the very people who had thrown the spears, demonstrating the power of Christ’s forgiveness.

This courageous, no-nonsense Christian was a pillar of coherent, committed faith—a beloved and sometimes controversial icon. And while things in the limelight might have looked golden, her suffering continued refining her in many different and unexpected ways.